Last of the Lake Schooners

They Came into Port Together

It was late in the afternoon on a summer day on Aug. 26, 1925. Not a cloud was in the sky. Suddenly on the horizon there appeared three lake schooners, under full sail, headed for Oswego harbor. At first some observers thought they were seeing an apparition or a mirage. But when it was discovered it was real, people thronged to the lower bridge to view a sight that hadn't been seen in decades. They came in on the wings of a northeast breeze from across Lake Ontario.

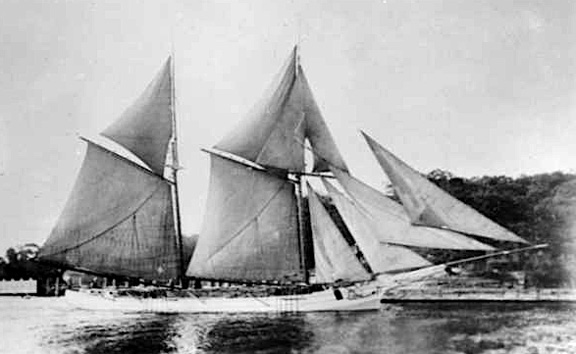

Full of years, the schooner "Lyman M. Davis" proudly sailed into Oswego harbor right well into the 20th century. View is looking east with Fort Ontario on the bluff overlooking the harbor.

Sailing Aboard the Lyman M. Davis

By Susan Peterson Gately

Great Sodus Bay on Lake Ontario has seen its share of maritime activity. Like Oswego, it was a coal port during the last days of working sail. Unlike Oswego it continued to export soft coal right through the 1960's. Its wooden loading trestle burned in a spectacular fire about 30 years ago. One of the last working schooners on Lake Ontario, the Lyman M. Davis called here regularly in the 1920's for coal. Sodus Point summer resident Guy Hance, who grew up by the lake in Pultneyville, sailed aboard her as a teenager. Guy has passed on to Fiddler's Green since I visited him in the company of another “old salt” who insisted that I hear some of his tales. He's been gone about ten years I believe.

But back in the spring of 1928 he and his sailing companion a teen aged Dick Burcroft (later to be a master mariner and captain of a freighter on the Murmansk run) went to Napanee Ontario where the ship had been laid up for the winter. The two teens spent several days reeving off lines bending on the heavy canvas and cleaning up the winter's grime from the old schooner's deck.

Hance recalled that the ship was by then decidedly work worn and weary ( She was burned off Toronto as a "spectacle" in 1934). Though by then she had been cut down to a bald headed rig "It was 75 feet from deck to cross trees. We had to go up there and bend on the sail. The ratlins weren't in too good shape. Once in a while one would break underfoot."

The crew of the Davis included two old hands Dolph MacFadden and "Tie Eye" Pippas along with four teen aged "green hands" seeking a bit of adventure. "The galley had an old wood stove range. The cook had a habit of spitting in the skillet to lubricate the eggs as there wasn't any butter on board..."

After several days of hard work, reeving, hauling, hoisting, patching, and dragging of gear, the Davis was some what ready for her season of work. Burcroft was aft in the yawl boat "towing" (pushing the schooner) down the winding Napanee River while Hance was at the helm when the ship went aground on a mud bank late in the day. "We rode the main boom back and forth but we couldn't get her loose. Then there came a little 'tide' the next morning and floated her off."

Hance was a husky farm lad well over six foot whose muscle was well used on this trip. He recalled the Davis had a little steam donkey engine but "they only used that to unload coal. It went chuff chuff-one bucket at a time. they'd lower it down into the hold, then a crew man would shovel the coal in. It took a long time to unload a schooner full of coal." The sails on the Davis were raised by “Norwegian Steam”, Hance recalled.

Once she towed out on the wider deeper waters of Quinte and Lake Ontario, sails were hoisted and she got under way. When she was light and had her centerboard up, Hance remembered, the old ship sailed quite well and didn't leak much.

After clearing the Bay of Quinte, the captain went below for a nap, worn out from the exertions of re- commissioning and running aground. He left Burcroft with the helm and as Hance recalled he told the teen "Dick I'm going to let you sail her across.” It was a nice night, It was a full moon the boat was light so she sailed right along, it was real nice sailing." Hance added "We got into Oswego the next evening." There he recalled bringing the engineless schooner in to the dock. "As we were coasting along side the dock, Pipas threw a light heaving line in ( to pass a heavier line over with). But the guy on shore took the light line and tried to snub her with that. She finally stopped but that line was smoking." Hance added "You wouldn't want to bump an old boat like that too hard against the dock."

When asked how he and Burcroft had gotten to know the schooner's captain, Guy explained that on a visit to Sodus Bay the summer before to load with coal at the trestle Dick and the captain had crossed tacks. "Capt M- was a real gentleman. But he had one weakness. One drink and he'd go on a binge, sometimes for two weeks he'd be gone. Once he came into Sodus in the middle of the summer, had the ship all loaded with coal and then went on one of his binges. Dick got acquainted with him then and sailed him around Sodus Bay with (his sloop) the Scud."

Hance recalled the Davis generally loaded coal at Sodus Point, Fair Haven, or Oswego and then took it to several different Bay of Quite ports, calling at Trenton, Belleville and Picton to unload. However, even before the Great Depression hit hard, the aging schooner was hard pressed to compete with the more efficient bulk carriers and the roll on roll off car ferries Ontario 1 and 2.

After a short stint as schoonermen, Hance and Burcroft went off on more adventures upon wider waters. They agreed to deliver a motor yacht down the inland waterway to Florida one fall which they did though not without a few "adventures" enroute. Once in this vacation spot for the rich and famous, both obtained jobs as crew on large yachts. Hance's duties included operating one of the yacht's launches.

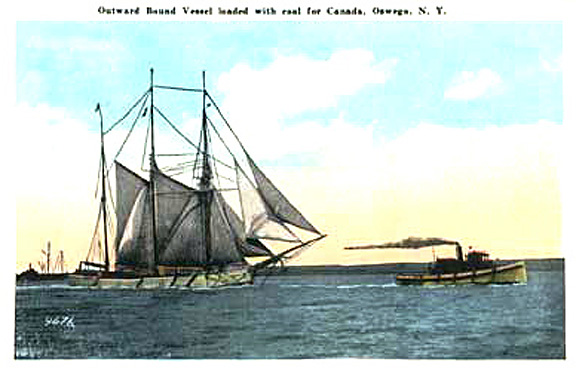

The days of sail on the Great Lakes ended where they began—in Oswego—even into the postcard era. Here, the schooner St. Louis is shown leaving the harbor under tow with a load of coal . She had been around since 1864.

The Lyman M. Davis of Napanee, a three-and-after, led the little band that also included the Mary A. Daryaw and Julia B. Merrill, both hailing from Kingston. For some years, these relics from the past had been working out their last days transporting coal between Oswego, Sodus and Fair Haven, to Canadian ports.

It was a sight that would not be repeated again anywhere on the Great Lakes. For the days of the sailing ship were gone. For more than two decades the numbers had dwindled until today there were only three or four still in active service. All of the schooners that were once home-ported at Lake Ontario ports had long since vanished. These three were among several "transplants" from the upper lakes, purchased by Canadian forwarders to replace worn out old carriers.

It was a sight that would not be repeated again anywhere on the Great Lakes. For the days of the sailing ship were gone. For more than two decades the numbers had dwindled until today there were only three or four still in active service. All of the schooners that were once home-ported at Lake Ontario ports had long since vanished. These three were among several "transplants" from the upper lakes, purchased by Canadian forwarders to replace worn out old carriers.

Everyone in Oswego knew they were getting their last glimpse of the past when as many as 50 such vessels visited this port in a single day. Old-time gray-haired sailors and skippers looked upon this "sight for sore eyes" perhaps for the last time. The day of the old-time "canvas" sailor was also quickly passing. The work that once took a crew of perhaps five or six men had long since been replaced by a donkey engine "fondly" known as the "iron jackass."

These weren't the sharp-looking, spotless schooners of yesterday. They were covered by years of grime. The decks and running rigging were covered with coal dust, the sails themselves resembling besmirched quilt work. No longer did the owners, skippers and crews take pride in "bright work" and varnished masts. They were tarnished ghosts serving out their last days of hum-drum existence.

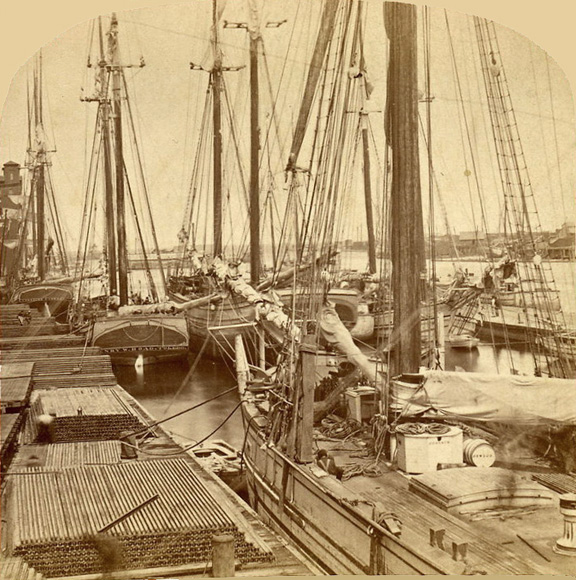

A classic view of schooners tied up on the west side of Oswego harbor in the 1870s, from an old stereoptican slide. Vessel immediately in the foreground is the "Cossack." At left, railroad iron awaits transshipment to the midwest.

Time was rapidly catching up with these remnants of the golden age of sail. It had obviously been years since these vessels were properly maintained. Their hulls were weak and leaking, and they sorely needed caulking. They were only kept afloat by a constantly working steam syphon.

The Mary A. Daryaw in its early days when it was known as the Kewaunee.

After the three-way race across the lake, the Davis, leading the pack, made her berth at the coal docks, soon breathlessly followed by the others. The three would continue to limp along for a few more years. It is ironic that Oswego and Kingston, which witnessed the arrival of the first sailing vessels on Lake Ontario, would also witness the last of them some two or so centuries later.

Another view of the Lyman M. Davis which is believed to have been the last lakes' schooner in commercial use.

The Davis, undoubtedly the best known of the three in Oswego, usually sailed into port under full sail, including flying jib, jib topsail, standing jib, staysail, foresail, foregaff, topsail, mainsail and main gaff topsail, making a total of eight sails on two masts.

Data on these "Last of the Last" Lake Schooners

Mary A. Daryaw built as Kewaunee 1866 at Port Huron, Mich., by J.P. Arnold for Murray & Slanson, Racine, two masts. Given last name in 1921. (U.S. Registry No. 14065; Canadian Registry No. 150481.) Ship dimentions: 124' x 27' x 8.' Lost at Four Mile Point near Simcoe Island, Oct. 15, 1927.

Lyman M. Davis built in 1873 at Muskegon, Mich. by J.P. Arnold for Mason Lumber Co., two masts. (U.S. Registry No. 15934; Canadian Registry No. 130436.) Ship dimentions: 128' x 37'3" x 11.' Last operating owner, Capt. John A. McCullough. Burned at Toronto as a public spectacle during Toronto's centennial celebration, June 29, 1934.

Julia B. Merrill built 1872 at Saginaw, Mich. by George Carpenter for Merrill & Skeele of Chicago, three masts. (US. Registry No. 75478; Canadian Registry Co. 126468.) Ship dimentions: 128' x 13' x 6.' Purchased by Henry Daryaw, Kingston, 1910. Last owner, William Peacock of Port Hope. Burned at Toronto as a spectacle, July 21, 1931.

_______

_______

Oswego Palladium-Times, May 28, 1927

Daryaw Steals Into Port Like Ghost of Past

______

Rochester Writer Sees Schooner In Light of Fading Romance

______

Close hauled it seemed on a wind of dream to those few who were fortunate enough to see her, the old lake windjammer, Mary A. Daryaw, two-master, 125-foot topsail schooner, Capt. Henry Daryaw commanding made the port of Rochester late Saturday out of Kingston after a cargo of coal and after a wait for a fairing wind cleared today, says Charles A. Rawling in the Rochester Times-Union.

The ancient schooner, sixty years old, is one of the three that remain on Lake Ontario and is the first sail-driven cargo vessel to make this port in ten years.

Without a camera or a whistle to do her homage she closed in silently on the harbor piers from the eastward in Saturday evening's dusk. her every rag was flying; foresail, mainsail, main gaff topsail, staysail, standing jib, flying jib, jib topsail They stood out "nigger-healed" and black with decades of coal dust, clear etched against a thunder squall making a gray and sullen in the western sky. A light southeasterly breeze canted her just enough to vie her an element of grace as she moved up the fairway burdened with dignity and years.

"Yes," Captain Daryaw, who has sailed fresh water for most of his life, admitted, "she is an old vessel, but we made the hundred-odd miles from Kingston in daylight. Come aboard. "

Once on deck she seems more than ever a movie setting. her spars, to one who accustomed to the spindly sticks of small yachts common to these waters, are as redwood tree trunks. The main topmasts towers 125 feet over the deck. The fly at the top masthead brushed the power wires strung across the river at the harbor mouth, as she came up stream. The mast hoops are large enough for a barrel. Her shrouds are cables as thick as a man's wrist and sweated taught, wonder of wonders, with lignum vitae dead eyes.

Catted against her bows are two gigantic anchors with stocks of wood and as big about as a man's body. Her long horn extends up and outward until it is a dizzy distance over the water.

There is no "dusty going" for the old vessel. The reef points as heavy as the main sheet common to these waters were pointed out in wonder. "Never use those at all," the Daryaw's mate announced. "Never as long as I've been windjamming on these lakes. "

The captain, mate, two men and the cook make up the schooner's crew. When the number was marveled at Dan'l Sofie, sixty-five years old, as straight as spruce and as hard as one of the dead eyes despite forty-five years in lake sailing vessels, patted an old serviceable steam winch affectionately on the drum.

"This iron jackass is as good as five lads, or maybe ten," he stated with such an emphasis of conviction that it made Captain Daryaw laugh. It seems it took Dan'l ten years to admit a winch worked in any other fashion save by five huskies. "Yo! Heave! Hoing," at the bars was worth deckroom.

Dan'l in his forty-five years of windjamming has seen all that fresh waters afford. He has been ice-bound in the Soo, taken off old coffin ships that opened up like berry crates in gales, has beat the straits of Mackinaw in pitch black night with the snow flying so thick that you could not see the binnacle and the lead, a chart and a good seaman's guess were all they had.

"Why only last year," the mate said, "I had an inklin Dan'l was down under the water along side and I fished around with a ten-foot pike pole. " He an eye toward Dan'l hedging forward to disappear down the companionway. "Sure enough, there he was spread out in the bottom like a frog. i fetched him out, and he was blue, as blue as the cook's whetstone. he said he was sick and fell in. That's what he said he was anyway."

Lashed into the shrouds was a long pole with a small wooden box nailed on the end. "That is what the old lady gets her bran mash from," the mate volunteered. "When she gets to leakin' we fill that with sawdust, shove it overside against the seam and the water takes the dust into the leak and plugs it. "

Perhaps Rochester will see one or two of the old vessels such as the Mary A. Daryaw again, but it it is doubtful. They have been down under the rapidly onrushing stem of progress for only a few generations but what they stood for is as dead as Atlantis. But to see one again is to realize as better men since Melville have said that "men have left the sea and gone into steamboats" and that most of the beauty and adventure has gone as payment for efficiency.

Mary A. Daryaw docked in Oswego harbor. Note the steam donkey engine on the deck to raise and lower sails.

Oswego Palladium-Times

Oswego Palladium-Times

Oct. 19, 1927

Mary A. Daryaw, Lake Schooner, Gutted By Fire

______

Leaving Only Two of Old Time "Canal" Craft in Commission

______

After almost half a century of faithful service on the Great Lakes, the last ten in the coal carrying trade on lake Ontario, the two-masted schooner Mary A. Daryaw was badly damaged by fire in Kingston harbor on Saturday morning, leaving behind only two more of a fleet of sailing schooners on Lake Ontario, which once numbered several hundred. One by one they have been wrecked on the rocky shores of Lake Ontario, burned to the water's edge or gone down with all hands while fighting the elements.

Local mariners pointed out today the only survivors of the famous old fleet of canal "hookers" are the Julia B. Merrill, hailing from Cobourg, over on the north shore, and owned by Captain "Bill" Peacock, and the Lyman M. Davis, owned and sailed by Captain John C. McCollough, of Napanee.

The Daryaw, which did her bit for years in and out of Chicago harbor, made her farewell trip across Lake Ontario last week when she carried 300 tons of coal from the Lackawanna trestle at this port to Kingston. It was the last trip of the season, and as Captain Harry Daryaw cleared the trestle and started across the lake, he promised to be back with his little schooner again next season.

Charles H. Eddy, in charge of the Lackawanna trestle, when asked today for an estimate of the number of sailing vessels that traded between Oswego and other Great Lakes ports in the palmy days, declared it would be impossible for him to venture a guess for the reason that in the old days boats not only plied this lake, but there was a large fleet trading between Oswego and the upper Great Lakes, particularly Chicago. He remembered one Sunday morning standing at the foot of West Fifth Street and counting 47 schooners with a fair wind and head for Canadian points across the lake for barley.

At the same time more than 40 sailing schooners remained behind in the harbor to be unloaded. That was a couple of years before the McKinley bill dealt a death blow to the importation of Canadian grain and marked the beginning of the end of the grain business which had made the port of Oswego one of the busiest along the Great Lakes.

But to return to almost the last one - the Mary A. Daryaw. Fire was discovered in her hold about 3 o'clock in the morning. For over six hours Kingston firemen worked hard to save her, but at the finish her sails were gone, her cabin was destroyed and great damage was done to her hold. She may be rebuilt, but it looks as though she had made her last journey. How the fire originated is unknown.

A 30-gallon drum of gasoline was on the boat, but this was thrown overboard to avoid an explosion. A five-gallon drum of oil was also on deck and when it broke and the oil spread over the deck the flames rose high and spread wide on the old schooner, and it was a hopeless task to save her.

Oswego Palladium-Times

July 18, 1928

Only Two Lake Schooners Now Left on Lake Ontario

_______

Davis and Merrill Last of Big Fleet That Operated Years Ago

_______

Is the day of the sailing vessel past? The answer to the question is made quite clear by merely taking along the Kingston waterfront, says the Kingston Whig. The steamer entering into the River St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario on her way to Montreal, with a cargo of grain from the Upper Lakes, or tied at one of the docks, discharging a cargo, and even the motorboats which daily make trips to the many island nearby, or the more luxuriant launches which carry pleasure seeks on excursions among the Thousand Islands, or for a cruise up the lakes, loudly proclaim that before the onward march of time and commerce, bringing along faster and more economical means of transportation on the water, the sailing vessel is doomed, and at the very present time is seriously threatened with extinction, in a matter of a few years.

Just Two Left.

Kingston harbor, which witnessed the arrival of the first white man's sailing vessel into the waters of Lake Ontario, seems also decreed to witness the last departure, as out of the dozens of vessels which at one time thronged these waters, only two are now in operation, and these are the schooner Lyman M. Davis and the schooner Julia E. Merrill. The schooner Mary A. Daryaw was also in the list until last year when she went out of commission.

The schooner Lyman M. Davis is owned by a Kingston man, Capt. Henry Daryaw, who started sailing about 30 years ago, and received his captain's papers in the year 1900. He owned and sailed the schooner Jamieson the year that he received his papers, sailed and owned the schooner Lizzie Metzner for five years, sailed the schooner J. B. Kitchen one year for James Richardson & Sons, Kingston; owned and sailed the schooner Horace Taber for five years, and sailed the schooner Julia B. Merrill, which went out of commission last fall, and now owns and sails the Lyman M. Davis, which is used in the coal trade between Kingston and Oswego.

Fore and Aft Schooner.

The Lyman M. Davis is the type of vessel known as a "fore and aft schooner," and was built at Muskegon, Mich. , by J. P. Arnold in the year 1873, and owned by William Munroe. . Her sails consist of a flying jib, jib topsail, standing jib, staysail, foresail, foregaff, topsail, mainsail, main gaff, topsail, making a total of eight sails upon two masts, the foremost with a height of 65 feet, topmast 60 feet, and the mainmast, height, 70 feet, topmast, 65 feet. She is 123 fee long with a beam of 27 feet, 2 inches; depth 20 feet 6 inches, and a draft, 11 feet. Her tonnage is gross, 195 tons, net, 185 tons, and she carries a crew of five men.

This vessel was owned from the time she was built until 1913 by William Munroe, when she was sold to Graham Bros. of Kincardine, who made her over to a British register. In 1919 it was sold by the Kincardine owners to Capt. John McCullough and C. H. Spencer, Napanee, and up to that time had never carried a cargo of coal, as she had always been in the lumber trade, but when the vessel was brought to Lake Ontario she entered into the coal trade and last fall was purchased by the present owner.

The Lyman M. Davis was rebuilt in 1912, and it is estimated that she will give a few years service yet, as she is still in good condition.

The other schooner which is still in operation on Lake Ontario is the Julia B. Merrill, which was in the lumber trade on Lake Michigan until purchased by Capt. Henry Daryaw, Kingston, who brought her to Lake Ontario and used her in the coal carrying trade for five years, and also carried feldspar to Charlotte, N. Y. She is now owned by W. H. Peacock & Co. of Port Hope, and is used for the coal carrying trade. This vessel is also a "fore and after" and carries the same sails as the Lyman M. Davis, but on three masts - foremast, height 60 feet; topmast, 55 feet; mizzenmast, height 55 feet; topmast, 50 feet. She has a length of 152 feet, width 27 feet, depth 8 feet 5 inches, has a tonnage of 200 tons and has carried 400 tons of coal. She also has a crew of five men.

These two sailing vessels and two sloops, Maggie L. and Granger, owned by Captain George and Arthur Sudds, Kingston, are the only ones now in operation for transportation purposes on Lake Ontario, so it is quite evident that as the horse had to make way for the automobile on the land, so must the old-fashioned sailing vessels make way for the faster and more economical means of transportation on the water.

____

____

The Lyman M. Davis -Last of the Great Lakes Schooners

By Richard F. Palmer

The Lyman M. Davis in Toronto, On September 29, 1930, newspapers chronicled the loss of the three-masted schooner Our Son during a gale off Sheboygan, Wisconsin, on Lake Michigan. Many maritime historians credited her with being the last schooner in regular service on the Great Lakes. It is true she was built as a laker and remained reasonably intact as a sailing vessel until the end, while so many of her ilk had long since been

cut down to barges and scows. But another old Lake Michigan native, the two-masted schooner Lyman M. Davis, owned by Captain Henry C. Daryaw of Kingston, Ontario, was still in service a year later, transporting coal across Lake Ontario.

The Davis remained in operation, unaltered, under full sail until the end of the 1931 navigation season, and possibly part of 1932. The Oswego Palladium Times carried a brief news item on September 4, 1931, proving the Davis was in service a year after Our Son was lost:

"The schooner Lyman M. Davis is loading at the Lackawanna coal trestle for the Bay of Quinte and the tug Salvage Prince and barge Warrenco will load anthracite at the same trestle for Kingston."

Despite its age, the Davis was remarkably well preserved and did not show her true age. She led a charmed life and various owners had lovingly maintained her. Even her planking was not scraped or scarred by time. Some sailors claim she was sound enough to last many more years.

This two masted schooner was built by J. P. Arnold at Muskegon, Michigan, in 1873. Her dimensions were 123 feet length, 27' 2" width and 9' 4" depth. She registered at 195 gross tons and 185 net tons. Her original U.S. Registry number was 15934. John O. Carlson, who made the spars, said the original masts were in two sections, totaling 136 feet from keel to tip and 114 feet above the deck. The lower part

was 86 feet and the upper another 50 feet. Both masts were the same height.

The Davis was just one of many built to haul timber following the the great Chicago fire of October 1871. Lyman Mason and Charles Davis, owners of the Mason Lumber company, owned considerable standing timber acreage in Oceana, Muskegon and Ottawa counties, Michigan.

Foreseeing an enormous market for timber, they drew up an agreement with Arnold to build them a schooner. During the winter of 1871-72, Arnold selected the choicest white oak he could find in the

Mason lumber yards and cruised their timber holdings for naturally shaped curved ribs and knees from standing trees. In the spring of 1872, Arnold assembled a crew of Swedish and Norwegian shipwrights

who had learned their trade in their native lands.

Captain E. J. Buzzard of Erieau, Ontario, recalled:

"My grandfather built her at the foot of Pine Street, Muskegon, in the year of 1873. I worked on her all winter, aged 17, and on January 26th, when I was 18, in the spring went on as an able seaman."

Buzzard said the lumber company had the distinction of cutting 250,000 feet of pine lumber in 24 hours. The Davis, he said, was skippered by Captain Fred Barnes for 11 years and never was dry docked:

"and in all that time no vessel, large or small, ever sailed by her, either in head winds or fair winds, not in gale or light winds, so she sure was some sailor."

The shipbuilders did their work well. The Lyman M. Davis was built to last and did. Much of her planking was two inches thick, 14 inches in width and 40 feet in length without a knot or imperfection. Sixty years later, the seams of the planks, where the oakum had been horsed in by caulking irons and mallets, still held. Captain William J. "Billie" Drumm of Muskegon, a retired tugboat runner, recalled the Davis was rigged as a fore-and-aft schooner carrying nine sails: foresail, mainsail, fore ‘and aft topsails, a staysail jib, flying jib, jib topsail and square sail, on the lakes known as a "raffee."

Unlike other schooners, the Davis had accommodations for several passengers -- often guests of Captain Barnes and his successors. Fred Trott of Muskegon said he made several trips on her when he was a boy and was quartered in the guest cabin. On one such voyage, on August 16, 1886, the Davis ran into a freak sleet and snowstorm on Lake Michigan. She was driven off course into the islands in the northern part of the lake far north of Muskegon.

Bert Barnes was on the job every day during construction of the Davis. He personally supervised the placing of every timber, plank and fitting. When she was finished, he asked for and was given command of her. She was launched at Muskegon in the spring of 1873. Isaac Arnold presented Captain Barnes with a barometer in a beautifully carved wooden case with a depiction of an anchor and coiled anchor line. This barometer remained aboard until the Davis was sold in 1918; then found a home with Murray Graham at Kincardine, Ontario. Captain Barnes was intimately acquainted with the vessel. He knew when to ease her and when she would stand a hard blow. He made sure she was immaculately maintained. Every winter, during lay-up, he inspected her frequently. If he detected problems they were corrected immediately. It is said the Davis was a consistent money maker for all her owners. She was a "fast sailor" and her record passages were known to every schooner man.

Eventually, she earned the reputation of being the fastest schooner the lakes. Newspaper accounts state she made three round trips from Muskegon to Chicago in a single week. Some feel, however, this is an

exaggeration as the labor involved would preclude this. It is also recorded that the Davis actually beat the steamer George C. Markham in a run across Lake Michigan from Kewaunee to Muskegon in the early fall of 1887.

The Davis was one of the vessels that picked up survivors of the wreck of the propeller Vernon which foundered on Lake Michigan on October 11, 1887. A few days later, the Davis was putting out from Muskegon, headed ee Kewaunee. At midnight, feeling the discomforts of a sore throat coming on, Captain Barnes went below to snatch a few hours sleep. Before retiring he pulled off a red woolen sock from his left foot and pinned it around his neck. When he was called to breakfast his sore throat was gone. He ate a hearty breakfast, bundled up warmly, and stepped through the companionway to the quarterdeck aft of the stern quarters.

The schooner, running light, seemed to skim over the clear green waves, their tops whipped to foam by the strong wind. Warm, well-fed dry, the spume and spray made his blood tingle; the whistling of the wind in the cordage was music to his ears. Captain Barnes was enjoying his exhilarating voyage. He thought how pleasant it was to sail the lake with a sturdy breeze and a buoyant ship. It was a sunny, brisk day for November -- blue sky, small white fleecy clouds moving high above the sparkling water. Everything was clean and fresh. Captain Barnes took a deep breath as he stepped on deck and said he seemed glad to be alive to enjoy this moment.

With his first instinctive glance he took in the set of the drawing sails, the angle of the wave direction and the cant of the deck. "Looks like we're cutting 16 miles of water to make four miles ahead, Onesime," Captain Barnes remarked to his helmsman, Onesime Marentette. "I geeve her leetle wheel an' sharp watching, eh, Captaine," Onesime replied. "Say Captaine! I teenk I see sometheeng ovair there." He indicated, with his chin, the direction over the starboard bow. "He ees not knee high, Captaine, but he ees there."

Sliding back the cabin hatch, Captain Barnes plucked his telescope from the becket, and, putting it to his eye, scanned the windward horizon te the north and west. He commented. "There is something, Onesime, and the way it's skimming around, it looks like somebody sitting in some kind of saucer. Keep 'er on this course 'till we come abreast. If it is somebody we will pull her into the wind and go alongside."

Closer inspection revealed two persons floating in the upturned cupola off the top of a steamboat wheelhouse. One man was crumpled and unconscious. His companion had arranged him, bottom center for ballast, and spread a neckerchief on his back, marked so that the game of crown-and-anchor could be played. A bearded sailor was doggedly tossing two pair of crown-and-anchor dice with all the absorption of a dedicated solitaire player. He was oblivious to the fact that the Davis was nosing alongside, the noise of the waves masking her presence.

A loud "hello" from above momentarily startled the lone mid-lake gambler. He made another throw before he fully realized help was at last at hand. A heavy cargo net was thrown down the side of the schooner. Two deckhands scrambled down and grappled the bouncing scallop. Lines were secured around the two men, and they were hauled aboard. The crown-and-anchor player was Ambrose Widfield. His companion was Levi Girardin. They were wheelsmen off the steamer Vernon. Widfield described the foundering of their ship and the passing of a down-bound steamer and a schooner without stopping. Girardin suffered from cold and exposure and was taken below and placed on a bunk.

To hold the Davis into the wind, Captain Barnes had his mainsail boom lashed midships. The only other sail being used on the schooner was the fore staysail. Lines were run to blocks on each rail, from the butt end of the staysail boom, then back to the capstan. Aided by the of the capstan, Captain Barnes manipulated the staysail to keep schooner’s nose into the eye of the wind and was actually backing down the lake while the rescue was being made. Within minutes, a bobbing lifeboat was sighted. The same rescue technique was successful. Mrs. Jeptha Van Kleek and her 20-year-old daughter, Alwilda, and two men, Vilas Brown and Aaron Hullard, were retrieved from the lake, all in good condition. The women had been wrapped in blankets on the floorboards by the stern thwarts; the men, warmly employed keeping the bow into the wind and bailing. Although tired. they suffered no ill effects.

The three able-bodied male survivors were fed and quartered in the forecastle. The women were taken to the after cabin, to aid the unconscious Levi Girardin. It is said the sharp-tongued mother insisted immediately that a mustard plaster be placed on Girardin's chest. The deughter, who had worked for a Chicago doctor, said lungs were located closer to a person's back, and that the plaster should go on his back. Both women were strong-willed. There was no compromise. So Girardin was made into a human sandwich.

Captain Barnes, bashful before so many fluttering females in his cabin, neither interfered nor took sides. During the off watch hours of the night, the captain sat with the patient until he regained consciousness. To relieve Girardin's obvious misery, Barnes stepped softly across the boards of the deck planking of the cabin floor, so not to wake the women curtained in their bunks. He reached for a bottle of brandy in Mrs. Van Kleeck's portmanteaus, from which he had surreptitiously noticed her sneaking the odd snort. He passed the bottle to Girardin for a swig to ease his pain.

The wind changed. Captain Barnes was called on deck. When he returned to the cabin the brandy bottle was empty and Girardin was again unconscious. This time sweat was rolling off of him almost in a cloud of steam. Captain Barnes fearfully filled the bottle to its former level with cold tea and replaced it.

By daylight, when the women stirred, Girardin awoke with the congestion in his lungs cleared and just a little headache. Both women argued all morning their respective remedies had cured the patient. But Levi Girardin winked owlishly at Captain Barnes, indicating that he credited his cure to the captain.

By noon the next day, the Davis made the Kewaunee offing and proceeded north for sea room, then luffed and rode downwind to the lumber dock. The rescued were reported and put ashore. By coincidence, or perhaps in reprisal, the schooner Blazing Star, which had made no effort to rescue the survivors, ended her days a month later piled on the beach at Bailey's Harbor. The rescue of some of the passengers and crew of the foundered steamer Vernon was a bright spot in the career of the Lyman M. Davis. When it was over, the crew took to loading her cargo and life returned to normal.

By 1897, Thomas Monroe of Muskegon owned the Davis. Her career was devoid of recorded incident until the spring of 1907 when Captain Hans Hermanson took over command following the death of Bert Barnes. Later she was sold to the Brinnen Lumber Company of Muskegon.

The name of Captain Bert Barnes and the schooner Burt Barnes was strictly coincidence. The Davis and the Barnes, the latter a three-master, were both owned by the Graham Brothers of Kincardine, Ontario. The schooner Burt Barnes was built by G. S. Rand of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and was named for John Wilburt Barnes, one of her first owners. The Davis remained the property of Monroe until the winter of 1912, when she was purchased by John, Donald, Colin, Angus and Alexander Graham of Kincardine. She was given the Canadian registry number 130436. As business for schooners on Lake Michigan slackened, the Graham Brothers made contracts to carry lumber, posts and slab wood from Lake Huron, Manitoulin and North Shore lumber docks to lower lake ports. The Davis was completely refitted by the Graham Brothers during the early months of 1913. On May 6, she was ready to sail once more.

William Brinnen went to the dock for sentimental reasons and offered to repurchase his old schooner plus a $500 bonus and costs of refitting. But the Graham Brothers wanted her for practical reasons and declined his offer. The following day, Mr. Brinnen died while the Davis sailed out of Muskegon.

The trip up Lake Michigan demonstrated to the new owners that they had made a splendid and seaworthy purchase. The wind came out southwest as she sailed out of Muskegon. The waves, curling up continued to run after each other, to reassemble and climb over one another, and between them, the hollows deepened. In an hour of calm of the harbor was forgotten, and instead of the quiet of the wind was deafening.

By midday, the schooner was completely snug for dirty weather. Her hatches were battened down, her working sails storm-reefed, and the raffle and topsails clewed up. She bound light and elastic. For all the of wind and waves she handled easily, as if amused at the scudding before the wind.

Angus Graham was at the helm; his brother, Colin, alongside. Alf Schaefer , a deckhand, and, and his wife, who was the cook, were snug in the galley. Jimmy Smith and Bob Whipbread, the other two deckhands, were dry in the forecastle. Alex Graham was forward, hugging the paul post, on lookout duty. It became quite dark overhead -- a stretching, heaving, crushing vault. Studded with shapeless gloomy spots, it appeared as a dome until steady gaze determined that everything was in rush of motion, draperies of darkness, pulled from a never-ending roll. The Davis fled faster and faster before the wind. The gale, the schooner and the clouds were all lashed into one great madness of hasty flight towards the same point. The waves tracked the schooner with their white crests, tumbling onward in continual motion. The schooner, though always being caught up, still managed to elude them by means of the eddying waters -- in her wake. In this flight the was of buoyancy -- the delight of being carried along without trouble in a springy sort of way.

They glimpsed Big Sable Point before darkness fell. Angus pulled closer to the wind and bore out to the west to clear the Beaver Island. On rushed the waves, one after the other, more and more gigantic in the blackness. They resembled a long chain of mountains with yawning valleys, and the madness of all the movement under a black sky accelerated the height of the clamor.

Colin joined Angus at the wheel. They called out loudly, laughing at their inability to hear each other in the prodigious wrath of wind. They could not see far around them either. A few yards off all seemed entombed in the fearful big combers with their frothing crests shutting out the view. Then, suddenly, a gleam of sunrise pierced the eastern clouds. The same fury lay on all sides. Then came sounds. Nearer, less indefinite, threatening destruction, and making the water shudder and hiss as if on burning coals. The disturbance increased in volume. Somehow the Davis was in between Gull and High Islands.

The sea began to gain on them, to "bury them up" as they phrased it. First the spray fell down on them from behind. Then, masses of water, thrown with such violence as must surely break everything in their course. The waves were shorter and higher and the wind roared little ridges up the backs of the big waves. Heavy masses of water curled over the rails in the waist and hammered the deck planks. Nothing could be distinguished over the side because of the screen of creamy foam that whipped off the tops of the waves. When the wind soughed, this foam formed whirling spouts. At length a heavy rain fell crossways, then straight up and down; soon all of these elements of destruction came together, clashed

and interlocked. Only one who has stood on a heaving deck through a blow on the Great Lakes can really relate to such an experience.

Angus and Colin, one on each side of it, held staunchly to the wheel. They were suited in their waterproofs, hard and shiny oilskins firmly secured at their throats and wrists with tarred strings. The rain and spindrift poured off them. When it fell too heavy they arched their backs and held on. They weathered High Island, then Trout, then Squaw Island, then - instead of luffing - they turned her head into the wind, came about easily and headed the bowsprit for the channel of the Straits of Mackinac.

As the Davis lay over on her new course the wind slacked off. The Mackinaw Passage was accomplished safely. It was as if Lake Michigan knew the Davis would never return and made an extra effort to hold her in home waters. Upper Lake Huron was crossed. The new moderate breeze held out of the same quarter and, with little tacking, the schooner entered Mississaga Channel and sailed down the North Channel, threading the islands easily to Little Current on the Manitoulin.

Here she loaded her first Canadian cargo. The bill of lading destined the first shipment of lumber for the Rouge River below Detroit. A fast passage was made down the lake. George "Fry" McGaw, skipper of

the fishing tug Onward of Kincardine was lifting nets over the West Reef. Spotting the down bound schooner, he threw over a heavy buoy at the end of the next net and ran out to the schooner to inform Colin Graham that he was the father of another son, Donald, born April 27, 1913.

The berth at the Rouge River was reached, the cargo unloaded and the Graham Brothers proudly sailed their "new" schooner into Kincardine harbor for the first time on June 12, 1913. The Lyman M. Davis immediately captured the hearts and imaginations of the townfolks, who for years claimed her as theirs; although she was kept fairly busy during the season and only wintered at Kincardine.

In new waters, like the gunslingers of the Old West, she was challenged at every opportunity for trials of speed by all of the remaining sailing ships. Only once was she beaten. In the fall of 1915 the Davis was loading posts at Silver Inlet on Georgian Bay. The three master Hattie Hutt, commanded by Captain Francis Granville of Southampton, was ready to sail. He wanted to race. He waited until the Davis finished loading.

The two schooners cleared the harbor together. During the first night out a gale of wind was encountered. Granville, having a three-master, was able to take in only his mainsail and keep canvas on his foremast and mizzen. Angus Graham decided it was prudent to take in the huge mainsail. He continued with only his inner jibs and reefed foresail. The Hattie Hutt passed Gratiot Light at Port Huron six hours ahead of the Davis. Like the Davis, the Hutt would end her days in the Lake Ontario coal trade, last running in 1926.

A Changing World

Work for schooners slackened after World War I. The Graham brothers were growing older. Colin and Angus accepted positions as mates on the Marquette and Bessemer Car Ferry No. 1, sailing between Toledo and Erieau. The other brothers still operated the schooner Burt Barnes, so when John A. McCullough and Cephus H. Spencer of Napanee, Ontario came along with an offer in 1919, they sold the Davis. The new owners took the old schooner proudly down the lakes and through the Welland Canal into Lake Ontario. She would be in the coal trade, primarily between Oswego, Fair Haven and Sodus on the south shore, and Kingston and the Bay of Quinte ports on the Canadian shore. She became a familiar and unforgettable sight.

William Markle of Napanee had a burning memory of serving as mate to Captain McCullough and told the author he became an expert at climbing the rigging and repairing masts. He vividly recalled a trip filled with all the excitement of old sailing days:

“On the 29th of November 1922 the storm signals were down, all the boats started leaving Oswego for home. We were the first in so we were the last to get out. It was about one o'clock when we left the harbor, the weather was fine. When we neared the False Ducks, a heavy snow came and we could not see four feet ahead of us. Captain McCullough took us past Timber Island, then we headed up into South Bay. Shortly, he hollered, but it was too late. The vessel was ashore on Waupoos Island. I went out on the jibboom and stepped on the shore in the woods.

“I went to a farmhouse as fast as a red squirrel to phone Kingston for a salvage tug. When I came back, the captain said we had better go to the lazarett deck, behind the cabin. There we took an auger and put a two-inch hole in the bottom. We let four feet of water in the hold so the boat would not break up in heavy seas.

“On the third day a tug arrived, and after three or four unsuccessful attempts it released us, the tug returned to Kingston for a lighter. On the seventh of December the tug returned with a lighter, and after removing a few tons of coal from the forward deck, the Davis broke free, and then the coal was put aboard and we headed for home. Near Glenora, Captain Ward and Bill Barret met us and we stayed with the schooner until we arrived home. As we were opposite Hay Bay, a squall came from the high shore and broke our raffee yardarm in two. I was elected to go aloft and disconnect the pieces. We arrived home on the 9th of December, safe and sound.”

Markle said life aboard the schooner was pleasant. "The harder it blew, the faster she went!" He fondly recalled the days of going aloft when the ship keeled out so far all he could see was the lake beneath him. His fondness for sailing vessels, especially the Davis, was reflected in paintings he created that were preserved in homes and offices in Napanee.

Markle said he also sailed on the schooners Katie Eccles and William Jamieson. He said considering her age, the Davis was in remarkably good condition. The crew, as always, was quartered in the forecastle cabin, with bunks on each side and a small stove for heat. The captain and his wife were in the aft cabin. Captain McCullough's wife was the cook and the ship was kept immaculate.

A donkey engine, commonly called an "iron jackass," was considered a labor saving device, and most of the latter-days schooners had them. Its primary function was hoisting and lowering sail. The weight of the gaff and sail were too much for a small crew of four men and a female cook. It would take three men just to hoist one of the jibs. The engine also raised and lowered the anchor which could weigh as much as a ton.

The Davis usually carried 248 tons of coal which could easily be loaded in about 35 minutes. Unloading her was a much slower and tedious job. Again, the donkey engine was used to hoist the coal out in buckets, each holding about a half a ton. Men in the hold shoveled coal into the buckets which the winch man would hoist up to a couple more men at the top of the coal sheds. They would trip the latch and dump the coal down a long chute. It was rather slow work and it took two and a half to three days to unload an entire cargo.

In 1928 Captain Henry Daryaw of Kingston purchased the Davis and continued her in the coal trade on Lake Ontario. By now, there were only a few schooners left still sailing the commercial trade on the lakes.

By coincidence, Daryaw also owned a sister ship to the Davis, the Mary A. Daryaw, formerly the Kewaunee. Like the Davis, she was built by J. P. Arnold, but at Port Huron, Michigan, in 1866. Up to the time she was burned as a public spectacle in Kingston on October 15, 1927, she is to have been the oldest lake schooner still in active service.

Some Chicago promoters suggested having the Davis at the Chicago World's Fair. She was taken out of service and slicked up with a fresh coat of paint. At the last moment, before sailing back up the lakes to home waters, the deal was canceled.

Captain Daryaw then seized the opportunity to sell the old vessel to the Amusement Association in Toronto. He had previously sold them the old schooner Julia B. Merrill which had been burned as a public on July 1, 1931. At the time, there was an outcry that the Merrill should be preserved for posterity, but it fell on deaf ears. Now, the Davis faced the fate. Unlike the Davis, the Merrill was practically derelict and too far gone to preserve. Her hull was badly hogged and her mizzen mast and raffee yard were gone. She only had four of her original 10 sails left when she was sailed from Kingston to Toronto.

Merrill dragged her age-wearied transom in the water as she into the harbor. She was minus one of her masts, all three of her and her hull had long since worn itself out.

Up to that time, Sunnyside had specialized in burning obsolete ferry boats and small craft. But when it was learned that the Davis was to be the next flaming spectacle for the crowds, there was a massive protest by preservationists, led by Toronto Telegram editor C. H. J. Snider, who, for more than 30 years wrote a weekly highly-acclaimed column called "Schooner Days.” He made repeated verbal attacks on the park's owner, Major D. M. Goudy, who shrugged them off. Snider said Goudy "has burned more ships at Sunnyside than Hector succeeded in doing before Troy." He labeled Goudy as "the Lord High Admiral and Fire Marshal of the recreation division of the Harbour Commission's fleet."

Snider's incessant journalistic attacks on Goudy raised such a furor that Goudy postponed burning the Davis until the spring of 1934. This was to give Snider and his ilk time to raise enough money to save her. Although Sea Scouts managed to keep her decks clear of ice and snow, winter of pounding against the seawall caused considerable, but not irreparable, damage. "Citizens of Toronto do not want the Lyman M. Davis demolished by fire to create a passing thrill for night-going sightseers, or to boost sales of hot dogs and peanuts," Snider wrote.

Thousands of people signed petitions against the wanton destruction of the old vessel. Scores of letters were published in local newspapers protesting this "act of savagery." City officials did what they could and were almost unanimous in their opposition. The community was still enraged over the burning of the Julia B. Merrill a few of years before. Although she was beyond preservation, many thought she should be allowed to sink in deep water or be beached and allowed to fall to pieces in the way of ancient wrecks -- a much more honorable end than burning as a public spectacle. Various fund drives were started, but not enough was raised to reprieve her. North America was in the midst of the Great Depression and coming up with ready cash was a near impossibility. Some suggested, however, that burning an old trolley car or two was preferable to burning the last schooner on the Great Lakes.

The schooner Lyman M. Davis in Toronto harbor prior to its destruction

(City of Toronto Archives)

The schooner Lyman M. Davis in Toronto harbor prior to its destruction

(City of Toronto Archives)

Goudy could not be persuaded to save the ship saying he would have torched it a year before had it not been for the intervention of Toronto's ignominiously coated with tar. On May 30, 1934, Goudy announced the park would sell the schooner for a reasonable sum to anyone who might wish to buy her; otherwise she would be burned during the coming season. Although no individual or group came forward with financial succor, Goudy's challenge produced a spectacle that attracted a tremendous crowd.

Her last Voyage

On her deck and in her rigging fireworks experts had placed powerful bombs and rockets. Eight barrels of kerosene drenched her timbers, Her deck and holds were piled high with dry wood and old crates. At midnight on June 29, 1934, a torch ignited a barrel of kerosene on deck and black smoke rolled skyward in a mushroom-like cloud. As the oil-soaked wood quickly ignited, the weather-beaten old craft was engulfed in flames from stem to stern.

Slowly, the blazing schooner was towed the length of the waterfront before drifting out into the bay. The banner, which for weeks had proclaimed her destiny, tossed like a pennant as the heat from the inferno rose. Finally high, leaping flames caught the bunting and it shriveled and disappeared against the dark sky. A tug towed her out into the lake where she burned to the water's edge before disappearing into the blackness.

Even in death the Davis refused to be obliterated. All of her above-water planking did not fall prey to the flames. Strangely enough, the unburned portion was the transom bearing the name of the vessel on large white letters on a black background. Name up, the four planks with as many portions of ribs, drifted away and finally landed on the west beach of Hanlan’s Island. This portion of the vessel would serve a useful purpose - providing a platform where bathers could wash the sand off their feet after their concluding dip.

Sources

Writings of Marine Historian C. E. Stein of Wheatley, Ontario.

Toronto Telegram:

February 14, 1931; August 12; September 1, 2, 9, 16, 23 and October 21, 1933; February 3, 10, 24; March 2, 3, June 1, 2, 30, 1934

Muskegon Chronicle, April 5, May 27, May 30, June 11 and July 5, 1934

Merchant Vessels of the U.S., 1885

Oswego Palladium-Times, October 19, 1927, May 25, 1931, April 7, 1932, February 2, 1934

Comments

Post a Comment